|

|||

|

|

|||

|

|

|||

| ||||||||||

|

|  CHAPTER 4

HELICOPTER AERODYNAMICS WORKBOOK

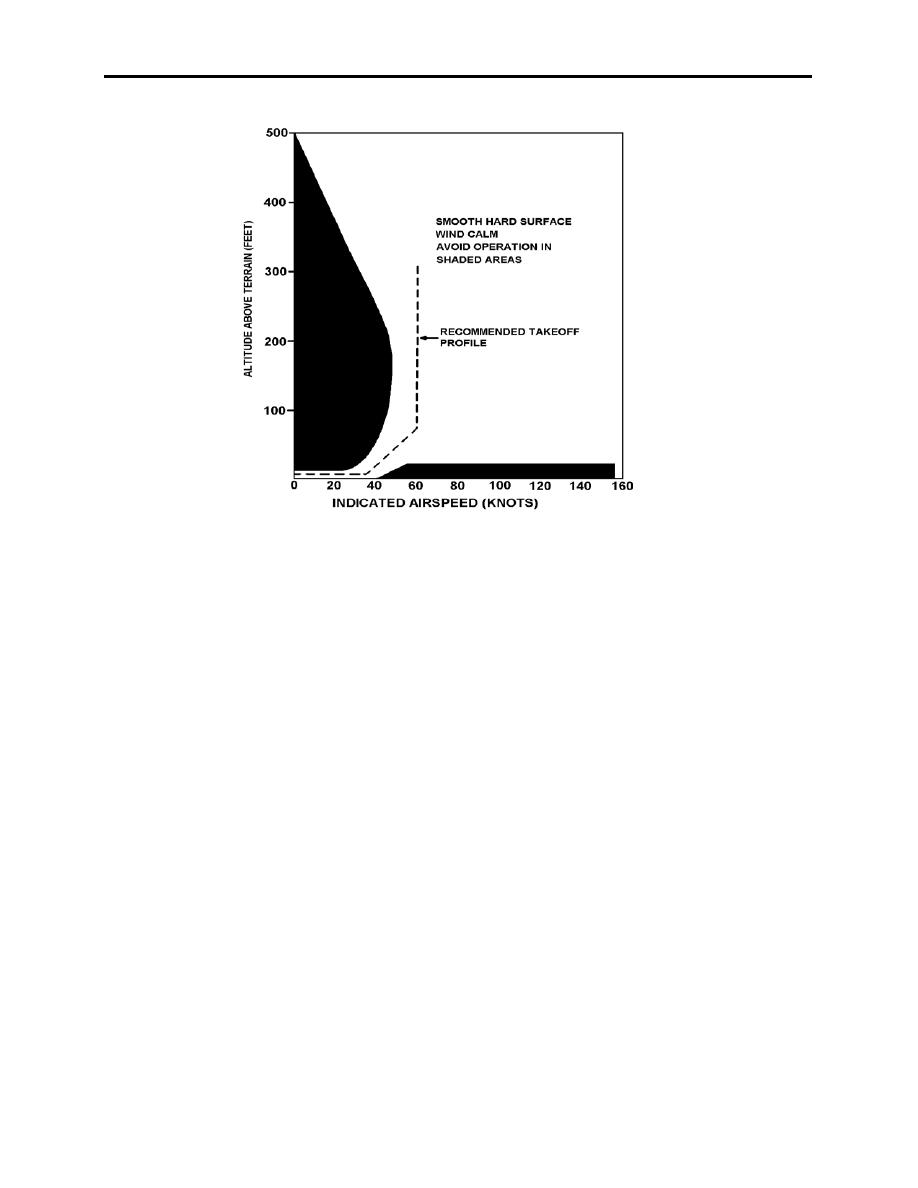

Figure 4-9

There are H-V diagrams for each type of helicopter. They are found in their respective

NATOPS Manuals. Helicopter pilots should be familiar with these diagrams.

Taking a closer look at the H-V diagram, we see several definite points define the curve, the

first being the low hover height. Up to this height, a pilot can handle a power failure by coming

straight down, using collective increase to cushion the landing. Above that altitude in

combination with low speed, the rotor blades will slow down and stall if collective setting

remains constant, or the helicopter will impact the ground too hard if collective is lowered.

Enough altitude does not exist to acquire enough forward airspeed by the time flare altitude is

reached to successfully execute a flare. This height is a function of: 1) the power required to

hover, 2) rotor inertia, 3) blade area and stall characteristics, and 4) the capability of the

landing gear to absorb the landing forces without sustaining damage.

The unsafe hover area runs from the low hover height to the high hover height. Above this

altitude, there is enough altitude to make a diving transition into forward flight autorotation and

execute a normal flare.

Beyond the knee of the curve, a power failure is survivable at any altitude above the high-

airspeed/low-altitude region. The three problems associated with the high-airspeed/low-altitude

region are as follows: 1) pilot reaction time, 2) lack of time and altitude for the induced flow to

reverse before ground impact, and 3) possibility of tail rotor stinger strike in response to cyclic

flare to trade altitude for airspeed.

4-10 AUTOROTATION

|

|

Privacy Statement - Press Release - Copyright Information. - Contact Us |